I have to admit this is a bit of a misleading title, since no-one else has access to the listener’s head but themselves! Still, it is our job as teachers to try and guess what is going on in there, using research findings based on empirical data to help us.

I want to give a bit of historical background, not because I want to show off my wealth of knowledge – and, incidentally, bore you to death – but because I have seen that certain old-fashioned beliefs still hold sway in both learners’ and teachers’ attitudes towards classroom listening practice.

Most of you have heard of “bottom-up” and “top-down” processing, concepts that attempt to picture what is happening inside the listener’s head and draw useful conclusions for classroom practice. Many of the teachers I’ve come across over the years still struggle with understanding these concepts. This can be because, despite the many diagrams used, it is not very clear what that vertical direction refers to: up/down towards what exactly? From a general idea to specific information? From the phoneme to the whole text? From using lower to using higher thinking skills?

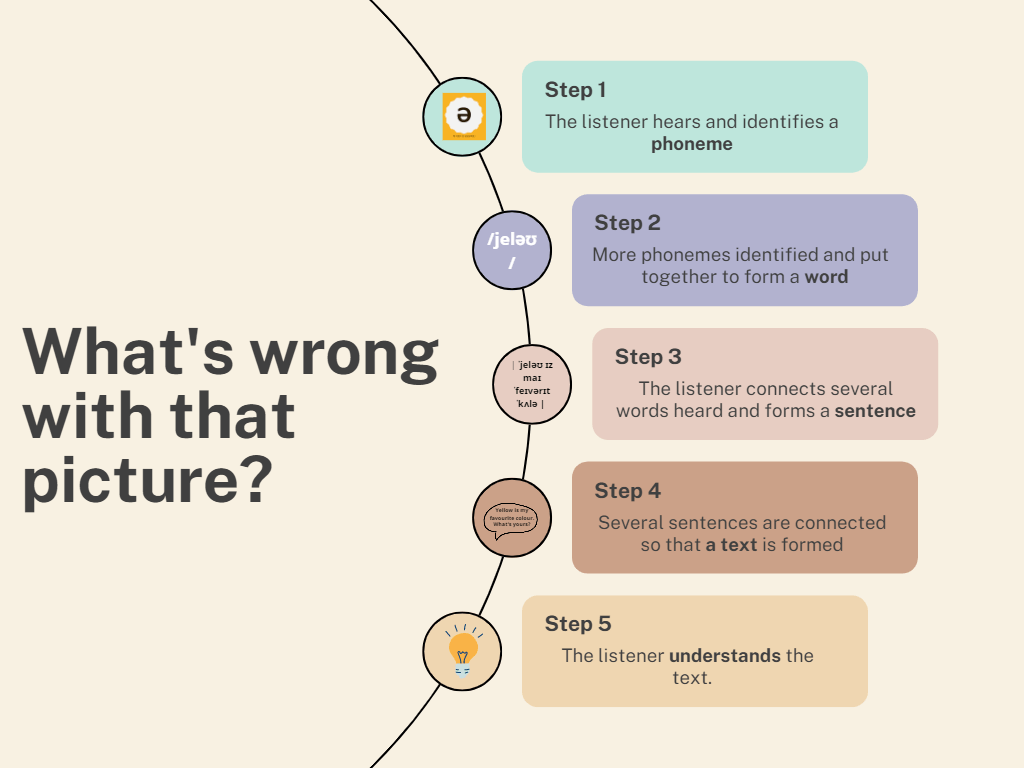

I believe that a linear representation does not necessarily serve better understanding of the listening process. I’ll now proceed, rather cheekily, with two different diagrams: one representing the more old-fashioned serial view of the listening process and another showing a more complex picture of what is happening inside the listener’s head. I’ll call them the line and the circle.

THE LINE

This view believes that the listener processes what they hear starting from the smallest chunk of sound, then adding them together to form words, which are then added to form sentences and eventually leads to the understanding of the whole text. We do not need all the empirical data of studies conducted with both L1 and L2 listeners, young and adult, beginner and advanced ones, to realise that if this were true, it would take the listener forever to decipher the speaker’s message, let alone formulate an appropriate response. Nevertheless, teachers still use recorded texts, paused and replayed ad nauseum, trying to get learners to understand every little thing they hear, all the time believing they are actually helping their learners develop their listening skills.

Unfortunately, this encourages the learners’ natural tendency to begin with processing the smallest amount of information and thus avoid information overload. Of course, this leads to some rather frustrating listening habits, like relying on the repetition of the information many times (never happening in real life listening) and the learners’ need to understand EVERYTHING before they can feel they’ve understood what the text is about (simply not true!).

Most importantly, it demotivates learners since it is an unrealistic and extremely demanding task. All this focus on detail encourages the segmentation of information, not regarding the text as a whole but as unrelated little chunks and relying solely on the acoustic input to decipher the message. No wonder learner confidence is shattered and motivation plummets!

We’ll contrast this with the circle in our next post.

I think you can guess my question for you now:

Have you found yourself following the line model, consciously or not, in your listening lessons?

I’m the first to admit that I have and that I have also found it extremely difficult to retrain learners to focus on other sources of information and regard the text as a whole.

Looking forward to your comments!

Alexandra